Digital Identity 101: An Introduction to Digital Identity in Public Benefits Programs (Draft)

This draft introductory guide explains the core concepts of digital identity and how they apply to public benefits programs. This guide is the first part of a suite of voluntary resources from the BalanceID Project: Enabling Secure Access and Managing Risk in SNAP and Medicaid.

March 2025

This document was drafted by project team members from the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the Digital Benefits Network at the Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation at Georgetown University, and the Center for Democracy & Technology for BalanceID: Enabling Secure Access and Managing Risk in SNAP and Medicaid. This project will build a set of voluntary resources that adapt NIST’s Digital Identity Guidelines to the needs and contexts of integrated online benefits applications, including SNAP and Medicaid, to help state benefits agencies make risk-based, human-centered decisions about authentication and identity proofing.

This draft document will ultimately become the introduction to the set of resources this project is building. The document aims to provide a description of core digital identity functions and outline when and how digital identity shows up in public benefits programs. This information is meant to be accessible to a general audience and public sector employees across roles.

Section 1: Audience and Approach

This document is intended to provide public administrators with a basic understanding of:

- The underlying concepts and technical aspects of digital identity, and

- How they are relevant to the delivery of public benefits.

We also hope this document will be useful to advocates helping individuals access benefits, nonprofits and industry partners supporting benefits technology implementation, and technologists looking to explain technicalities of digital identity to non-technical audiences.

Information about the use of account creation and identity proofing in public benefits programs is drawn from the Digital Benefits Network’s 2024 research, “Account Creation and Identity Proofing in Online Public Benefits Applications.” The core concepts, terminology, and ideas are derived from NIST’s Digital Identity Guidelines and have been modified to be as accessible as possible to all readers, regardless of technical background.

Section 2: What is Digital Identity?

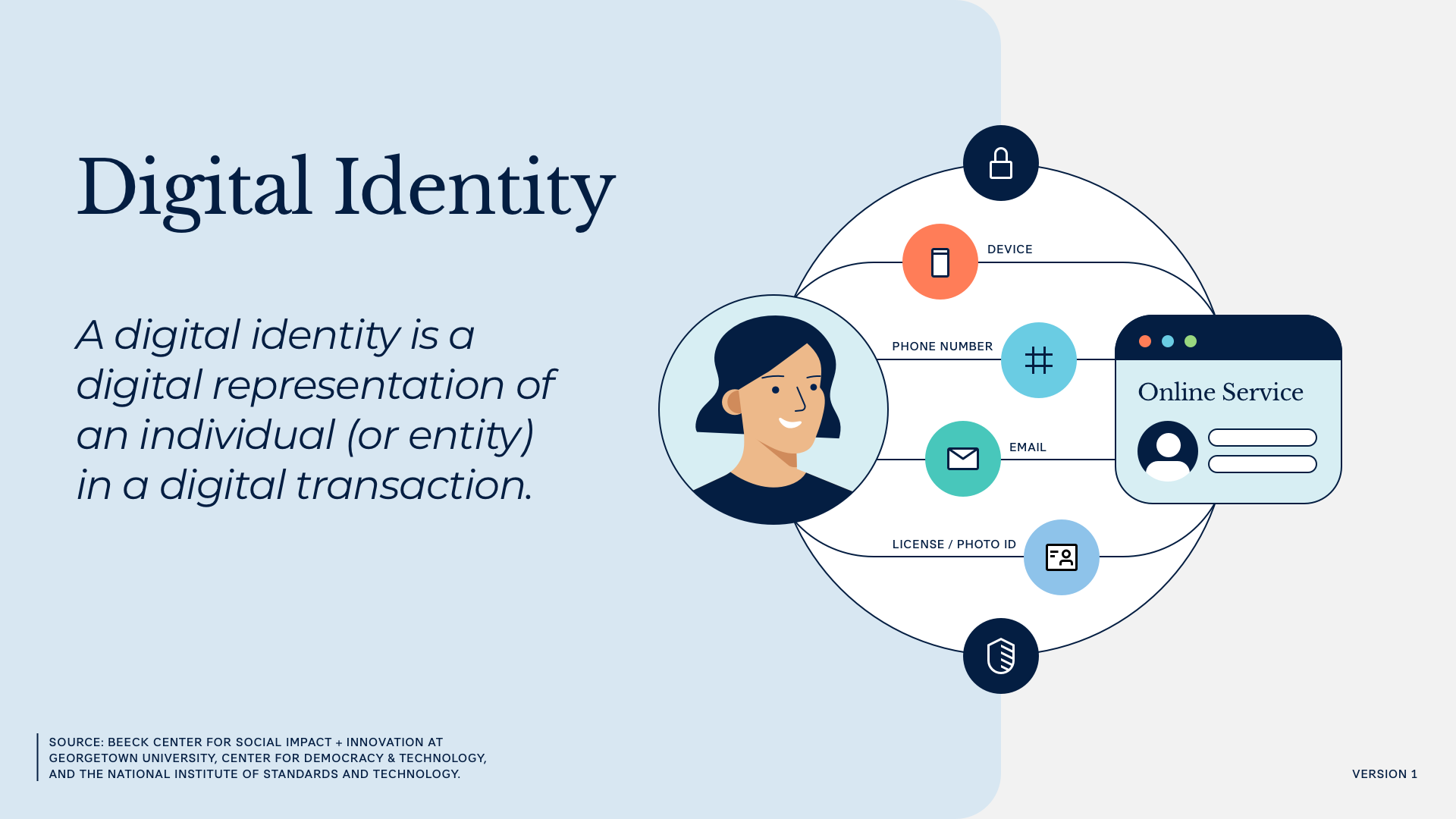

Digital identity is a digital representation of an individual (or entity) in a digital transaction. The most common form of digital identity is a username and account created for an online application or service.

In public benefits, a person may be asked to create an account when applying for or managing their benefits (though it is not always required). This can be for security reasons, or to provide a way for the user to manage their interactions with the benefits agency. For example, updating their email address or phone number for basic communications.

Not all digital identities are equal. How much a service provider can trust an identity is based on how an identity is created and protected. Benefits agencies must aim to strike a balance between (a) ensuring someone is who they say they are, while (b) not erecting barriers that make it difficult for them to access and manage their benefits.

Core Concepts

Digital identity is composed of three core concepts, all of which have implications for security and trustworthiness.

- Identity Proofing: Who are you? Identity proofing increases confidence that the digital identity a new user is claiming belongs to a real person and is being used by the intended person. Identity proofing defends against impersonation attacks aimed at misusing someone’s identity or identity data to gain access to online services.

- Example: Requiring an applicant to upload a government-issued ID, validating that their name, address, and date of birth match an authoritative source (like DMV records), and verifying that the ID actually belongs to the person who is presenting it.

- Authentication: Are you the same you? Authentication asks users to confirm identity when returning to an online service. Authentication offers a quicker means of proofing for users and defends against account takeover attacks, where someone attempts to gain access to a pre-existing digital identity.

- Example: Requiring a returning user to input a username and password.

- Federation: How do I share information about you? Federation provides a convenient way for users to access services using digital identities that they already have.

- Example: Allowing a user to log into a food delivery app with an existing account hosted by a third party email platform.

Accounts Without Identity Proofing

You don’t always need to verify someone’s identity to let them create an account, save information, or return to a transaction at a later date. A public-facing benefits portal can allow an applicant to create an account and save an in-progress application to return to later—all without completing identity proofing. The requirements you choose should always balance access needs with security needs.

How you use each of these three concepts will depend on the context and risks of the particular service you’re aiming to protect. For example, to determine how to use identity proofing, authentication, and federation for a public benefits portal, you’ll assess:

- what information is available to a user upon logging in (e.g., personally identifiable information [PII], past financial transactions, vital documents, or employment or credit history); and

- what actions they can take when using the service (e.g., applying for or cancelling program enrollment, setting payment preferences, sending communications).

The following sections describe each core concept in more detail.

Section 3: Identity Proofing

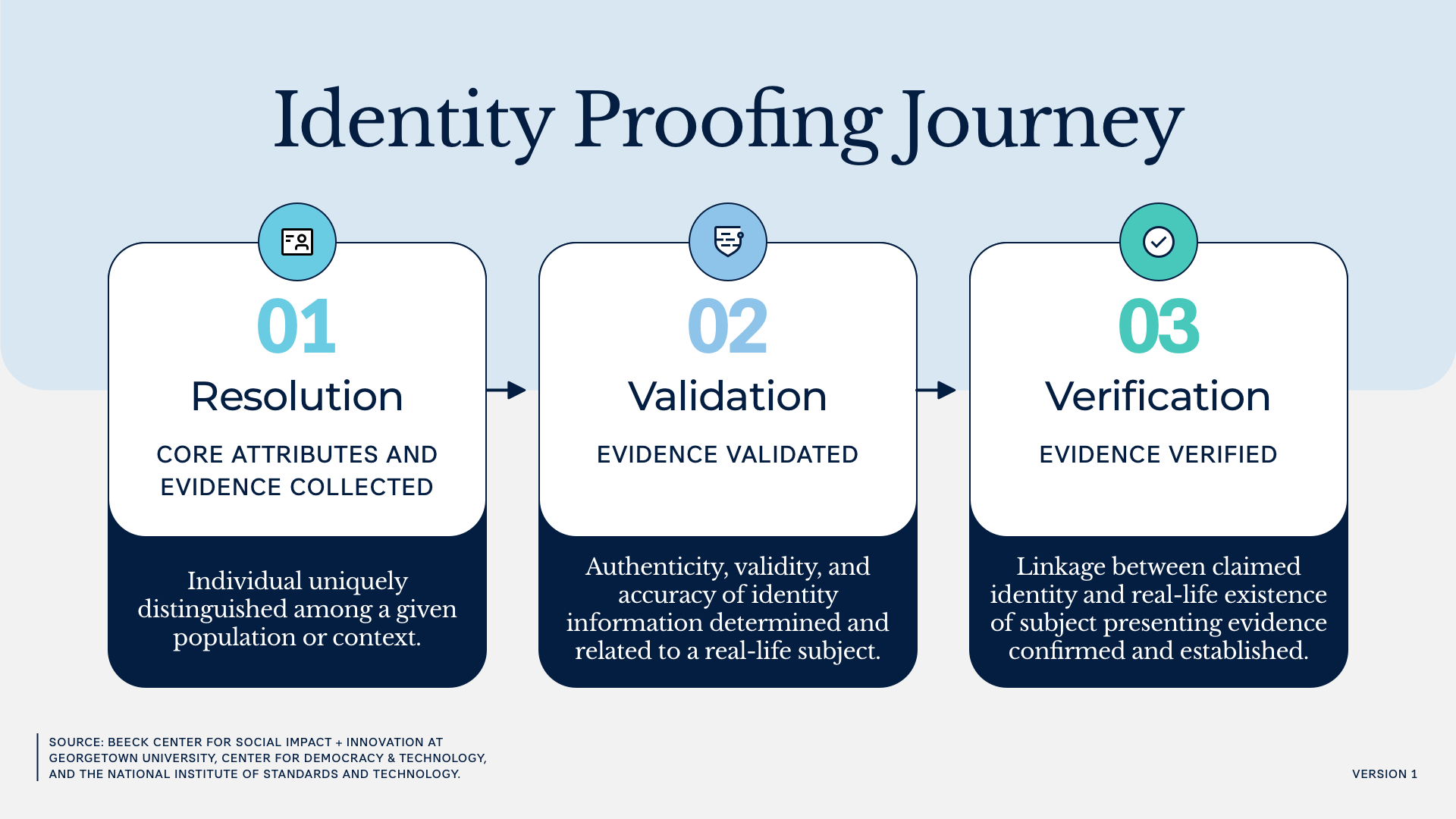

Identity proofing is the process of determining who is interacting with an online service. In the context of public benefits, identity proofing is often conducted by a public agency (or a company working on their behalf) to assess if an applicant or current enrollee is who they say they are. After gathering relevant identity evidence, this process involves:

- Determining that they are the specific person the agency intends to offer services to (a process called resolution);

- Confirming that the information and evidence they provide is real and accurate (a process known as validation); and

- Confirming that the person participating in the identity proofing is the person represented in the evidence (a process known as verification).

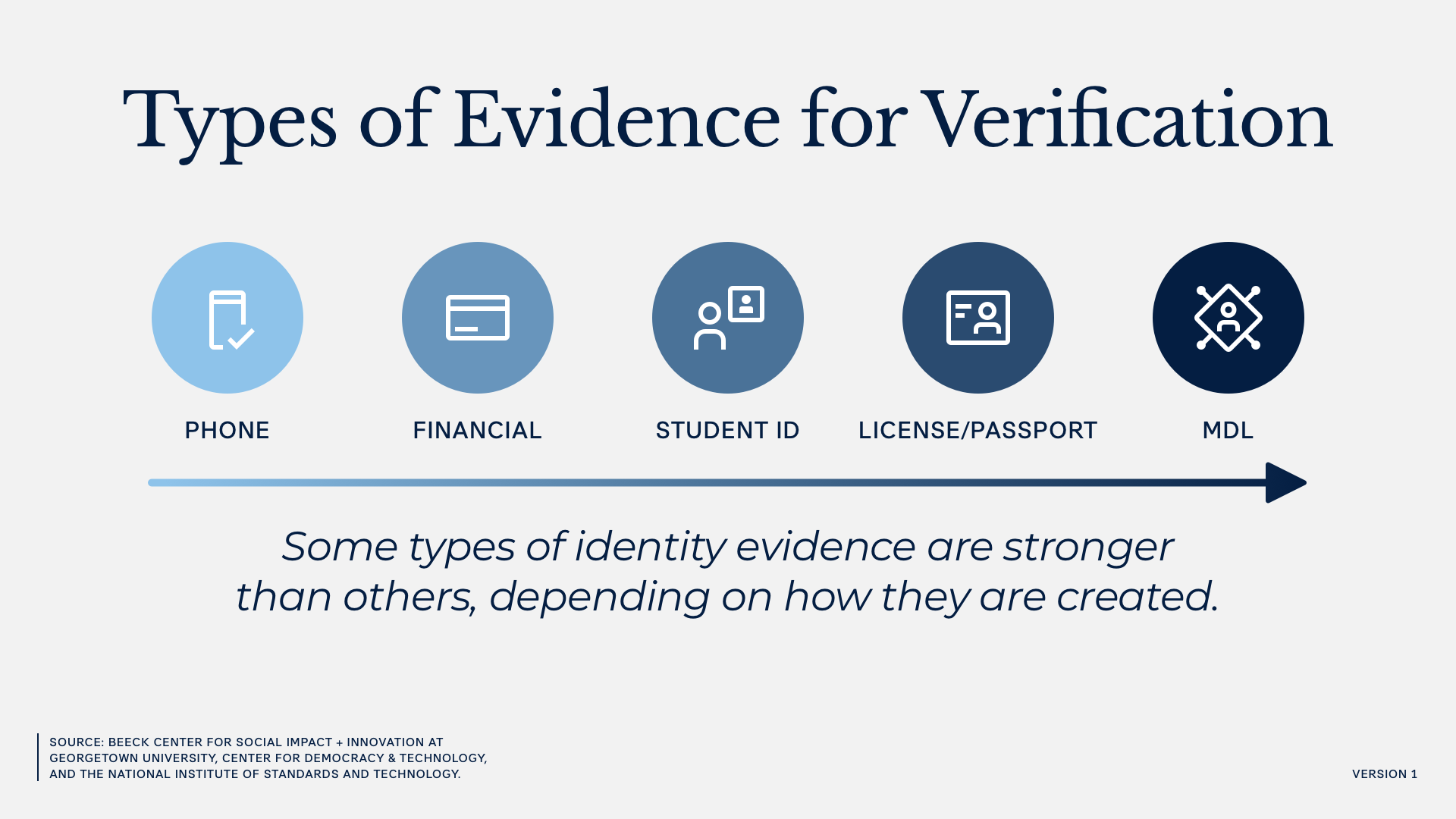

Understanding Identity Evidence

Identity evidence is documentation or information that proves someone is who they say they are. Identity evidence can be documents (such as a phone bill) or digital artifacts (such as a mobile driver’s license). Not all forms of identity evidence are considered equally strong. For example, a person might have to provide more documents and information to get a driver’s license than to get a school ID. In that case, the driver’s license would be considered a stronger piece of identity evidence.

However, not all scenarios require the same strength of evidence. For example, you’ll likely need more robust identity evidence to open a bank account than to secure a public library membership.

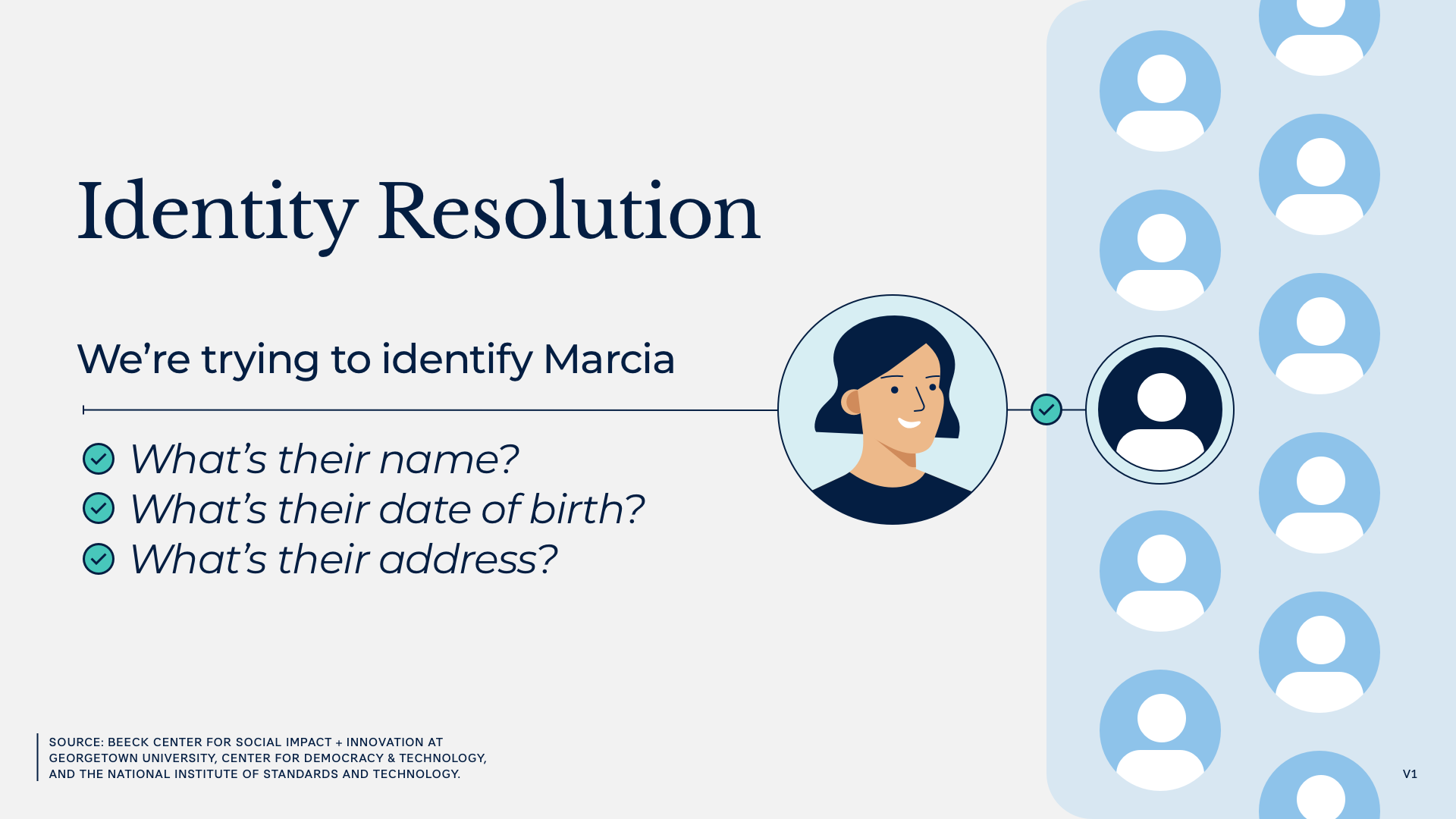

Step 1: Identity Resolution

Identity resolution is the process of extracting enough information from identity evidence to determine that an applicant is a real person and that they are the specific person your organization intends to interact with. Exactly what data you need will depend on your population and benefits system, but might include date of birth, address, phone number, or a government identifier like a Social Security number or a tax identification number.

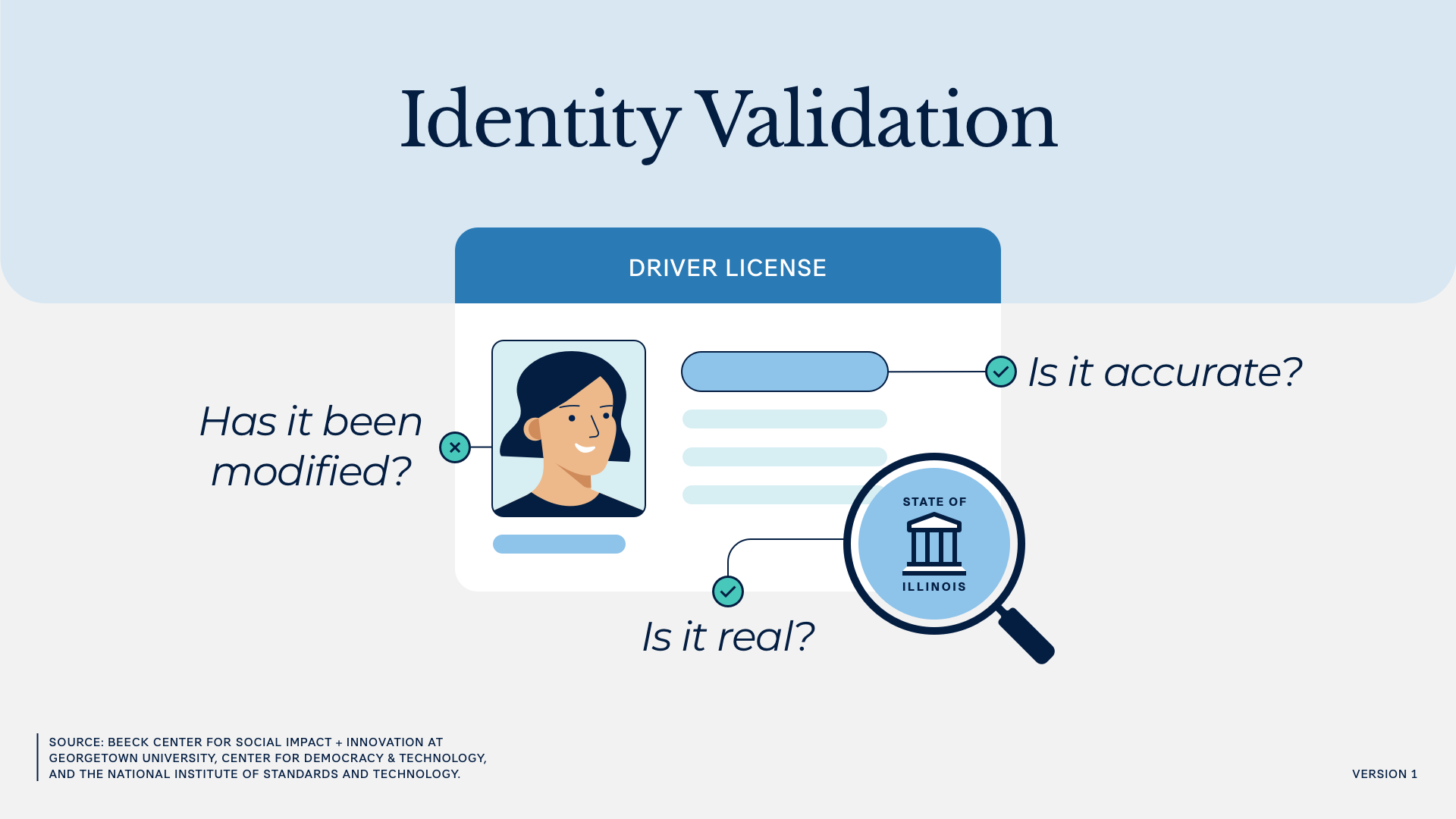

Step 2: Identity Validation

Identity validation means reviewing identity evidence to confirm it is real, accurate, and in fact connected to the person trying to access a service. This usually happens through two steps:

- Evaluating the presented evidence to determine it is real (evidence validation); and

- Reviewing the information provided by the applicant—through data entry or as captured from evidence—to determine it is accurate (data validation).

Evidence validation is typically completed using remote technologies that scan documents for indicators of authenticity (e.g., physical security features like holograms) or by trained professionals who inspect evidence for signs of authenticity.

Data validation is done by comparing the collected information against reliable sources to determine its accuracy and relevance to the applicant (e.g., comparing a driver’s license number to DMV records).

Evaluate the options for both evidence validation techniques and sources for data validation to determine which are appropriate for your organization.

Identity Data vs. Eligibility Data

Identity data allows benefits agencies to understand the identity of the applicant. Identity includes things like date of birth and Social Security number—attributes that help to uniquely identify a person within a population.

Eligibility data allows benefits agencies to determine an applicant’s eligibility for program participation. Eligibility data might include things like income, employment status, and assets.

Identity data does not need to include eligibility information, and vice versa.

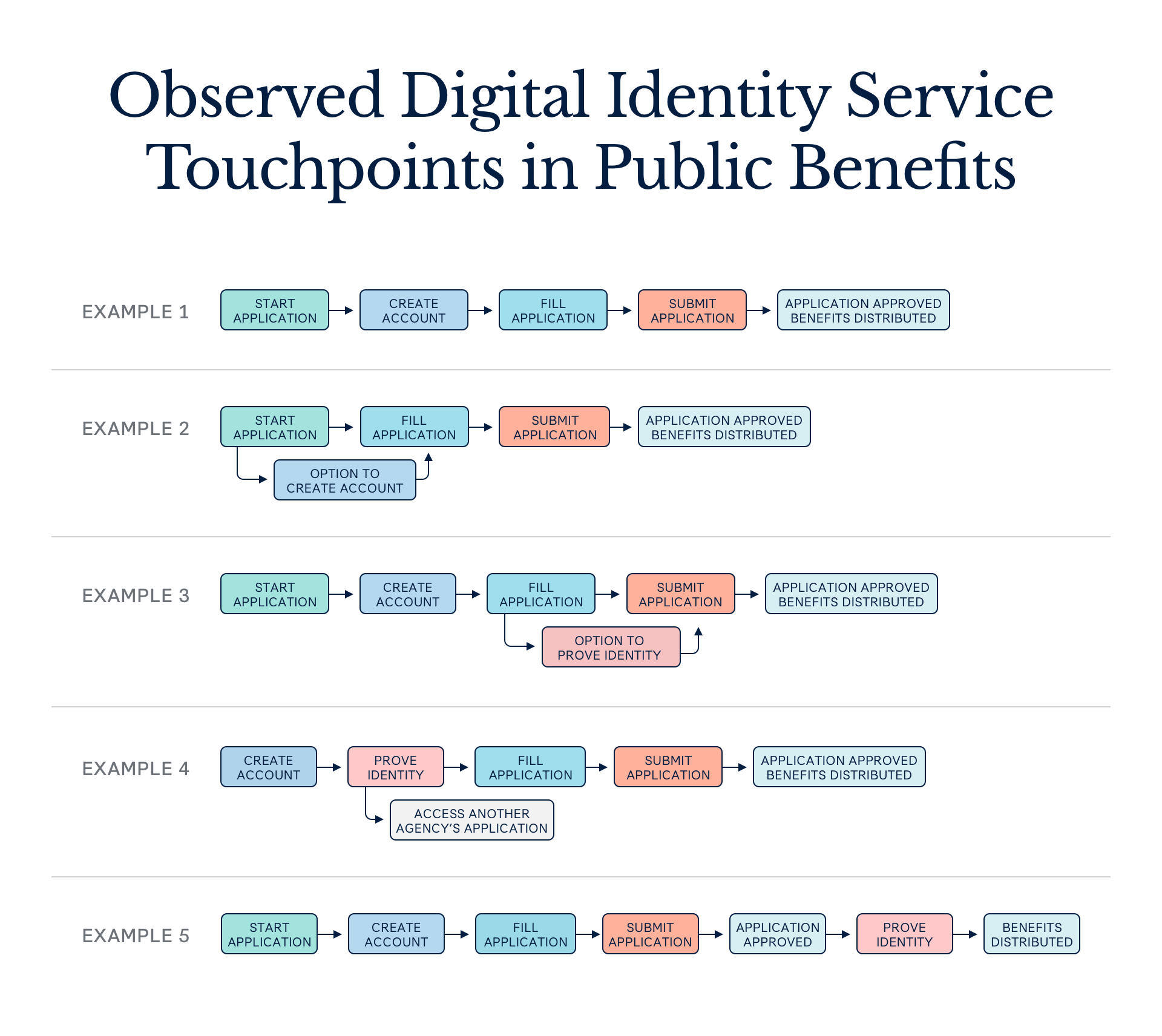

But, timing is everything. It’s important to note that requiring someone to verify their identity (with identity data) before they submit an application essentially makes identity verification an eligibility requirement—which is typically beyond what is required by federal law. This, in turn, can pose a barrier for those who are eligible but cannot at that moment verify their identity.

Step 3: Identity Verification

Identity verification is the process of confirming that the person presenting identity evidence is the person who owns that evidence and not someone attempting to impersonate them.

There are many ways to verify someone’s identity. These include:

- Visually comparing the person to an image present in the evidence they provide;

- Biometrically comparing them to the image on the evidence they provide (i.e., using an automated algorithm);

- Asking a person to return a code sent to a phone or physical address;

- Asking a person to authenticate a verifiable digital credential, such as a mobile driver’s license; or

- Asking a person to return the value of a microdeposit made to a financial account.

When choosing which method(s) to use, aim to balance security and usability. The methods above vary in strength, as well as how accessible they are to users with varying access to identity evidence and technologies. You will need to evaluate verification methods depending on the risk of your transactions and the populations you serve.

Rethinking Knowledge-Based Verification (KBV)

Knowledge-based means for proving identity—such as questions about someone’s credit history—have become less secure over time, with vast volumes of personal information exposed by data breaches in recent years.

KBV can also be challenging for users to complete correctly, and is biased toward users with strong credit histories.

Read more about why alternative approaches should be prioritized in “Removing Barriers to Access From Remote Identity Proofing” by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) and “Data Protection:Federal Agencies Need to Strengthen Online Identity Verification Processes” by the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

By the Numbers: Identity Proofing in Public Benefits

Whether an online transaction requires identity proofing—and where in the transaction the identity proofing process takes place—will depend on the type of information exchanged and the level of risk. In the context of public benefits, identity proofing sometimes happens when a beneficiary first applies. In other cases, agencies collect additional evidence about someone after they submit an initial application, such as during an interview or in the process of reviewing an applicant’s information.

A few important notes about the current status of identity proofing in the public benefits context1:

- Identity proofing requirements are most common in initial applications for unemployment insurance (UI)—in 2024, at least 58% of UI applications required completing some identity proofing steps to apply.2 This is followed by applications that include Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) Medicaid—52% of applications that include MAGI Medicaid prompt identity proofing steps.3

- Biometrics are most commonly used in UI applications. Only one non-UI application (South Carolina’s Medicaid application) uses biometrics.

- Compared to 2023, more state agencies implemented “optional” identity proofing at the point of an initial application in 2024. This means users can choose to skip online identity proofing or, if they are unable to complete online identity proofing, can proceed with the application and verify identity later.

Section 4: Authentication

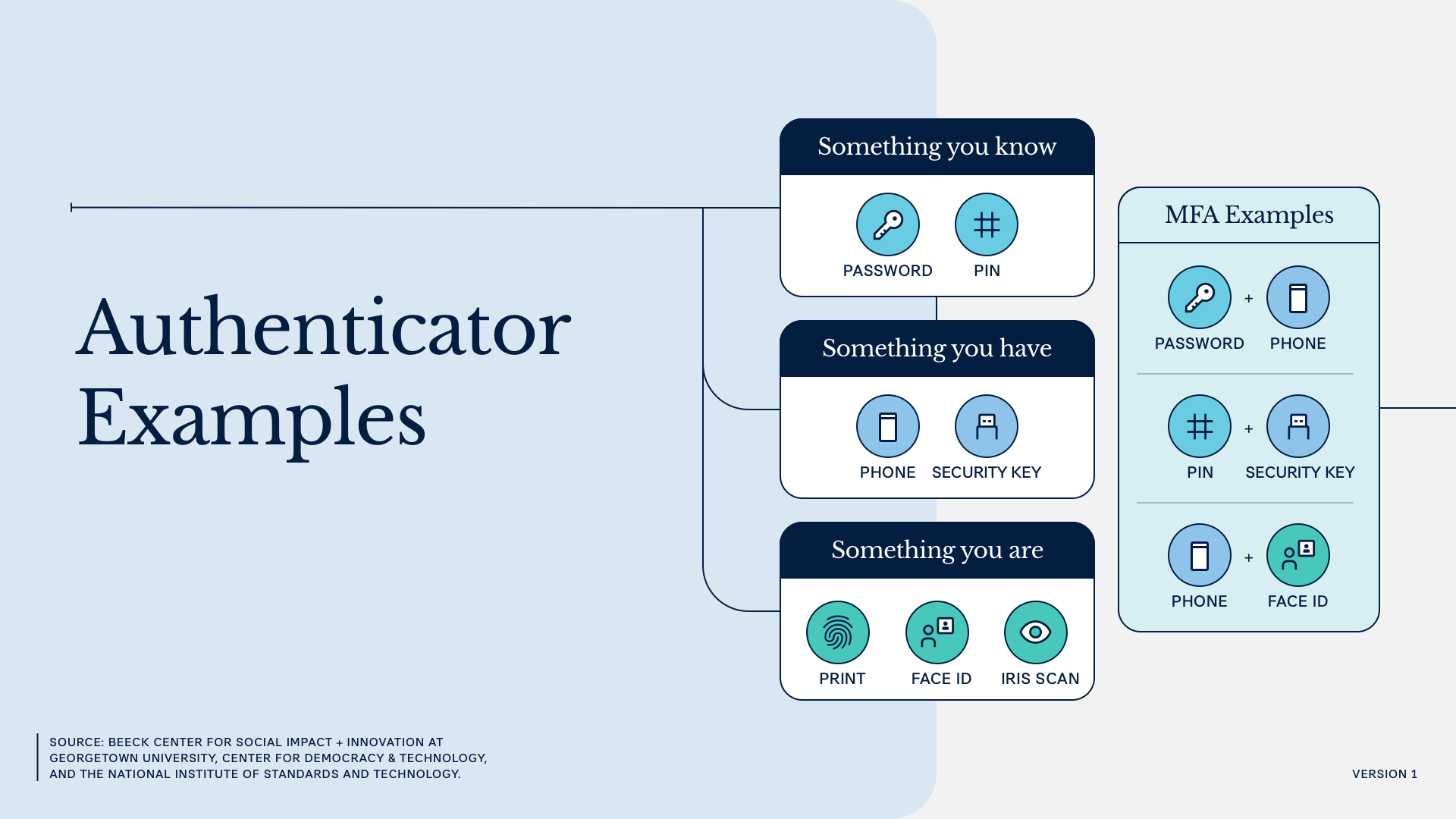

Authentication asks an enrolled user to demonstrate their identity when returning to an online service by presenting “authenticators.” These, such as a password or PIN, help verify a user’s identity by representing or containing information known only to that person and the service that is authenticating them. The different categories of authenticators—something you know, something you have, and something you are—are called “authentication factors.” (This is where the phrase “multi-factor authentication” comes from.)

In a public benefits context, an applicant might be asked to create an account when first applying, and then asked to authenticate their identity by entering a username and password (something you know) when logging back into the system.

| Factors (categories of authenticators) | Description | Authenticators |

|---|---|---|

| Something you know | A piece of shared knowledge between the authenticating system and the user | – Password – PIN |

| Something you have | A physical device or piece of software that the user can prove they have during authentication | – Text code – Security token – Passkey – Smart card |

| Something you are | An inherent trait or characteristic that can be used to identify and authenticate the user (i.e., a biometric) | – Face (FaceID) – Fingerprint (TouchID) |

Authentication systems provide controls that prevent account takeover attacks, some of the most common and scalable attacks on identity systems. However, systems that rely on a single factor are more vulnerable to automated attacks, guessing, and phishing. Multi-factor authentication (MFA) systems combine multiple authentication factors when protecting an account and are inherently more secure.

Balancing Usability and Security with Multi-Factor Authentication

MFA is a critical security tool for online accounts that protect sensitive information, such as PII, payment information, or health information. There are tradeoffs, as many MFA methods can present usability issues for people with limited technology access or internet bandwidth. Luckily, not all online services have a level of risk that warrants MFA.

When deciding whether or how to use MFA, be sure to consider not only your security objectives, but also the technology access and digital literacy of your user populations. For example, if your online service gives users access to sensitive information, you might offer MFA as a recommended but voluntary option for those who can easily complete MFA when logging in.

By the Numbers: Account Creation and Authentication in Public Benefits

Whether an online transaction requires security measures like account creation or authentication will depend on the type of information exchanged and the level of risk. Given the types of data and transactions hosted by online benefits portals, most do ask users to create and authenticate accounts.

- In 2024, 75% of the 162 online applications for SNAP, TANF, MAGI Medicaid, WIC, Child Care, and Unemployment Insurance required users to create an account in order to apply for benefits online. The most common type of program to require account creation is UI.4

- Most online benefits applications across programs (79%) prompt people to use at least one authentication factor in addition to passwords, such as a one-time passcode sent to an email or phone, security questions, or an authenticator app.5

- Sixteen percent of applications use security questions as the only authentication factor.6

Avoiding Security Questions

As with KBV, security questions can be challenging for applicants while lacking significant security benefits. NIST does not recognize security questions as an acceptable authenticator because answers are often exposed in data breaches.

Section 5: Federation

In some cases, your organization can confidently accept a user identity that has been proofed or authenticated by a trusted external party. To do so, you will use federation. In this process, a third party completes identity proofing and authentication and sends a message (called an assertion) verifying the identity and filling in any personal information needed to complete the account creation.

(This document introduces the concept of federation but does not go into technical details, such as which protocols to use.)

Federation outsources key security practices to an external entity. This requires a substantial degree of trust. But it also can bring immense value to benefits agencies and their users, including letting people reuse the same credentials for multiple services.

Federation can involve commercial services. Agencies can also leverage state systems to repurpose credentials used for a different state service. This can limit costs for states overall and ease burdens for users who have identities established for other state services. These setups are often called single sign-on options (SSOs).

By the Numbers: Single Sign-Ons in Public Benefits

As noted, SSOs let people use a single set of credentials for multiple government services. Public agencies have implemented SSOs to improve user experience and limit the costs of managing redundant accounts.

- As of 2024, 36 of 162 online benefits applications across programs were using government SSOs that enabled applicants to use the same login as other government services in the state.7

- However, as the Digital Benefits Network8 and the CBPP9 have previously written, if an SSO has strict security requirements, like mandatory identity proofing, these will be applied across multiple services despite differing risk levels and security needs.

Trust Agreements

Trust is critical when establishing a federated relationship. Trust is typically formalized through “trust agreements,” in which state agencies and external parties outline their shared expectations for privacy, security, and customer experience of any services provided. In the context of federation, trust agreements can take many forms—contracts, interconnection agreements, memorandums of agreement—but must define both parties’ requirements and expectations.

Tech Trend to Watch: Digital Wallets

In recent years, device-based wallets for storing verifiable credentials have emerged. In the US, the most prominent example of these credentials is the Mobile Driver’s License (mDL): a digital representation of a traditional physical driver’s license, designed to operate in the digital world.

An applicant with an mDL carries a powerful tool for proving their identity online. While these technologies are in their early days, benefits agencies should explore what mDL programs exist in their state, and consider how mDLs might supplement or improve existing identity proofing methods.

Look out for developments in this area—a variety of projects are working on standards to support other options for identity credentials beyond mDLs.

Section 6: Risk Assessments and Assurance Levels

Risk assessments are critical for determining how much, if any, proofing and authentication to build into your online service. They also provide a means to programmatically document decisions and balance competing risk factors, such as security, privacy, fraud, and usability. NIST’s Digital Identity Guidelines provide a framework for assessing risk in a broad range of use cases.

The framework recommends the following steps:

- Define the online service: What does your online service do, and what needs protecting? How does it fit into the larger experience of applying for, managing, and administering benefits?

- Conduct an impact assessment: What will be the impact to your service and users if a bad actor gains access through proofing, authentication, or federation failures?

- Select initial assurance levels: What baseline security controls should your identity management system include?

- Tailor and document assurance levels: What aspects of the baseline controls need to be modified to account for user privacy and accessibility, or specific threats?

- Continuously evaluate and improve: How effective is your identity management system, and where can it be improved?

What is an assurance level?

In the context of digital identity, an assurance level indicates the level of risk facing your service and its users. These levels are categorized as Level 1 (low risk), Level 2 (moderate risk), and Level 3 (high risk). Each level comes with a set of “baseline controls”—security measures to help protect your service, such as requiring multiple forms of identity evidence for identity proofing, or multi-factor authentication for returning users.

NIST breaks assurance levels into three different types: identity assurance, authentication assurance, and federation assurance.

Regardless of whether your agency chooses to use NIST’s risk management framework and assurance levels, it is critical to document your process for assessing system risks when selecting controls. Arbitrary selection of controls can easily lead to unnecessary friction for users, security theater, or substantial vulnerabilities being left unaddressed due to limited understanding of the risk environment.

Multidisciplinary Approaches to Successful Risk Assessments

Effective risk management requires a diverse set of viewpoints.

Risk management practices managed exclusively by security professionals can fail to consider how to best support external users. Risk decisions made purely by product or project teams may not take into account the complex threat environments facing benefits programs. Online services designed without privacy and customer experience in mind might be secure and fraud-resistant, but never adopted.

To build an identity management system that balances a benefit program’s security, fraud, privacy, and customer experience realities, it is essential that teams across your organization participate in your Digital Identity Risk Management process.

Additional Resources

To see how this work was put into practice, explore the following resources and examples in the Digital Government Hub:

Roadmap: NIST Special Publication 800-63-4 Digital Identity Guidelines

Revision 4 of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication 800-63, Digital Identity Guidelines, responds to the changing digital landscape that has emerged since the last major revision of this suite was published in 2017.

BalanceID: Enabling Secure Access and Managing Risk in SNAP and Medicaid

A collaborative research and development project to adapt NIST’s digital identity guidelines to better support the implementation of public benefits policy and delivery while balancing security, privacy, equity, and usability.

What is Digital Identity?

In this updated primer, the DBN introduces the concept of digital identity, and provides brief snapshots of digital identity-related developments internationally and in the U.S.

2024 Edition: Account Creation and Identity Proofing in Online Public Benefits Applications

In December 2024, the Digital Benefits Network published an updated open dataset documenting account creation and identity proofing requirements across online SNAP, WIC, TANF, Medicaid, child care (CCAP) applications, and unemployment insurance applications, to help the broader ecosystem identify promising practices and areas for improvement in public benefits identity management.

Combatting Identity Fraud in Government Benefits Programs

This post argues that for the types of large-scale, organized fraud attacks that many state benefits systems saw during the pandemic, solutions grounded in cybersecurity methods may be far more effective than creating or adopting automated systems.

Digital Identity Verification: Best Practices for Public Agencies

This report outlines best practices for public agencies to implement secure, equitable, and privacy-conscious digital identity verification systems.

Get in Touch

Email us at balanceID@georgetown.edu with questions or comments.

- The data below comes from the Digital Benefits Network’s 2024 research: Elizabeth Bynum Sorrell, Ariel Kennan, Anvitha Reddy, Isabelle Granger, Miranda Xiong, Olivia Zhao, and Quinny Sanchez Lopez, “2024 Edition: Digital Account Creation and Identity Proofing in Public Benefits Applications,” Digital Benefits Network, December 4, 2024. The review looked at identity management practices in online applications for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), MAGI (Modified Adjusted Gross Income) Medicaid, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), Child Care Assistance (CCAP), and Unemployment Insurance (UI) across all states and territories.

↩︎ - There are 53 UI applications across states and territories. ↩︎

- There are 53 applications that include MAGI Medicaid across states and territories. ↩︎

- 2024 Edition: Digital Account Creation and Identity Proofing in Public Benefits Applications. ↩︎

- 2024 Edition: Digital Account Creation and Identity Proofing in Public Benefits Applications. ↩︎

- 2024 Edition: Digital Account Creation and Identity Proofing in Public Benefits Applications. ↩︎

- 2024 Edition: Digital Account Creation and Identity Proofing in Public Benefits Applications. ↩︎

- Elizabeth Bynum Sorrell, “Promising Practices for Digital Identity in Public Benefits,” Digital Benefits Network, November 15, 2023 (updated January 10, 2025). ↩︎

- Symonne Singleton, “Remote Identity Proofing: Better Solutions Needed to Ensure Equitable Access,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 27, 2024. ↩︎