Implementing Benefits Eligibility + Enrollment Systems: Key Context

This publication explains the fundamentals of state IEE systems—including the technology, opportunities, risks, and stakeholders involved. It is a resource for state officials, advocates, funders, and tech partners working to implement these systems.

Introduction

In the United States, if someone is applying for one public benefits program, chances are high that they are eligible for another. But, until recently, most state benefit applications were “standalone,” requiring applicants to apply for each program separately. To apply for multiple programs using standalone applications, applicants have to navigate redundant processes, like answering overlapping application questions, participating in interviews, and repeatedly verifying the same documents. This lack of integration has been tied not just to a drain on applicant and staff resources, but also lower enrollment rates for eligible people who might not (a) be aware of cross-program eligibility, or (b) have the time or energy to complete multiple applications (Code for America, 2025).

In a 2019 blog post, Code for America presented the struggles faced by a hypothetical young mother who recently lost her job in Connecticut, a state that lacked an integrated benefits experience at the time:

“To apply for… benefits, the mother would need to spend more than an hour to apply for just SNAP [the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program] and TANF [Temporary Assistance for Needy Families]. The application does not work on her mobile phone, so she may have to visit a library or borrow a friend’s computer to apply online… [She then] has to find 45 minutes to fill out a separate Medicaid application… To apply for LIHEAP [the Low Income Energy Assistance Program], she would need to look up her local Community Action Agency, make an appointment by phone during business hours, and then show up in person to complete more forms.”

But in recent years, a growing awareness of these inefficiencies has resulted in increased investment in integrated eligibility and enrollment systems (IEEs). In 2025, Code for America reported that 35 states now offer integrated applications of at least three programs.1 How states actually build and operate these systems is a source of considerable complexity—and the documentation of these processes is often restricted to internal parties, with limited public research available. To offer insight into states’ processes and challenges, the Digital Benefits Network (DBN) at the Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation at Georgetown University launched Implementing Benefits Eligibility + Enrollment Systems, a research initiative documenting states’ processes for building and maintaining IEE systems, including how they interpret and translate policies into the software code that informs these systems.

Throughout summer 2025, the DBN conducted interviews with 24 leaders from seven states that operate or are building IEEs for core programs. This publication serves as a primer for related in-depth publications from this research about the current and future outlook of IEEs. It outlines key background information about IEEs shared by states during our research—defining what an IEE is, the relevant technology landscape, and the roles and stakeholders involved. We hope this will provide foundational context for states pursuing IEE systems, including new additions to state IEE teams, as well as those in state legislatures, other state offices, advocates, and civic tech partners.

This publication is part of a series on Implementing Benefits Eligibility + Enrollment Systems. Read more about our research process and find the other publications in the series.

Note: Under our research protocol, we are not disclosing which states we spoke to or attributing specific information or quotes throughout this publication.

Defining IEEs

IEEs allow people to apply for multiple public benefits programs using one process. Programs include means-tested programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Medicaid, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP), and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) for which clients are likely to have overlapping eligibility. While all IEE systems share the goal of streamlining applications, what they look like depends on many factors, including funding, project team composition, legacy technologies, vendor contracts, and state policies. When we talk about IEEs, we’re describing systems that offer some type of integrated benefits experience, in contrast to fully standalone applications that have distinct systems for acquiring and processing applicant information.

McKinsey has defined IEEs as “the enabling technology behind state-level [health] and human services programs in the United States. The core of an [IEE] is automated rules and a case management and workflow system that encodes logic to enable timely and accurate eligibility determinations for Medicaid and other human services programs.”

In some states, integration occurs primarily on the front-end, where a unified application (online portal or paper application) allows clients to apply for multiple benefit programs simultaneously through a single interface. The information provided by applicants is then routed to multiple program-specific backend systems for processing, which may be owned and managed by different state agencies. Other states have adopted a more comprehensive integration model, where a unified front-end application connects to a single integrated backend system that handles eligibility determination across multiple programs. This architecture consolidates both the public-facing experience and the underlying administrative infrastructure, creating a more deeply integrated benefits delivery system. Both models, and all the variations in between, come with considerations around how policy rules are revised, how data is shared, and the role of agency workers in services like eligibility determination and ongoing case management.

Value of IEE Systems

As noted above, IEE systems are understood to offer improvements in terms of efficiency and access. The state leaders and staff members we interviewed echoed and specified what they see as the value of IEE systems, including:

- Seamless delivery of multiple benefits. States recognize that many individuals and families have multiple needs and qualify for multiple programs. They aim to provide one seamless point of entry for all of the programs offered through their IEE, reducing the amount of repetitive labor clients will have to do throughout the application and enrollment process. One state leader described this as part of their effort to “stop requiring people to continuously prove their poverty to us.”

- Streamlined caseworker experience. Multiple states mentioned how an IEE benefits caseworkers, streamlining casework by allowing them to process client information more efficiently. When working in a state without an integrated application, caseworkers must help clients complete and process separate standalone applications for each program they are eligible for.

“We allow for agencies to bring their program to the platform and leverage our overall architecture to more effectively access data that we have for various programs, [which can] impact their ability to deliver and also provide more of a seamless point of entry—for not only our … customers, but our caseworkers and state employees that are working with various benefit programs.”

State Leader

- Improved client experience. Related to the goal of more seamlessly delivering multiple benefits, states described striving for the best quality of service for clients, facilitating maximum enrollment and limited churn for eligible individuals. To this end, several states mentioned leveraging human-centered design in constructing better user experiences and service design.

“We really wanted to have our clients … stop [having to] repeat themselves over and over as they navigated through different programs in the department, [and] have one front door they could go to as … there are so many different pathways to connect to our programs. … None of our programs are talking to each other at the same time. … It really goes back to expanding access for our clients—providing faster, [higher] quality benefits or services—and then improving the overall client experience.”

State Leader

“When people find themselves in a life circumstance, where … they may be in need of healthcare [and] benefits, they likely also are in need of food or cash assistance. And so we use [our cross-agency coalition] as a way to figure out how we can focus on the customer, and really look at the processes they’re going through.”

State Leader

Across our conversations, states expressed the importance of delivering accurate and timely benefits to be good stewards of taxpayer dollars. Attempting to balance access and accuracy in IEE systems is one of many strategies that states are using to improve service delivery and reduce the potential for waste, fraud, and abuse.

Risks Related to Eligibility and Enrollment Systems

Eligibility and enrollment systems rely on a set of overlapping technologies and information sources to intake and verify applicant and client information, determine eligibility, issue notices, and communicate with individuals in a timely fashion. As noted above, state agencies see clear benefits to IEE systems, including simplifying client experiences, increasing access to multiple programs, and improving state worker experiences. Whether or not a system is integrated to encompass multiple benefits programs, the current processes of translating eligibility rules into computer systems, and operating these systems to enable eligibility determinations, introduces the potential for error. When systems make mistakes, individuals can be disenrolled and lose benefits. Moreover, given the scale of these systems, a tech or design flaw can impact hundreds of thousands of individuals. The risks outlined below are informed primarily by existing research and journalism.

- Automated decision-making that harms clients

IEE systems enable eligibility determinations, and incorporate automation to varying degrees.

We can think about IEE systems as automated decision systems using scholar Rashida Richardson’s definition:

An automated decision system is any tool, software, system, process, function, program, method, model, and/or formula designed with or using computation to automate, analyze, aid, augment, and/or replace government decisions, judgments, and/or policy implementation. Automated decision systems impact opportunities, access, liberties, safety, rights, needs, behavior, residence, and/or status by prediction, scoring, analyzing, classifying, demarcating, recommending, allocating, listing, ranking, tracking, mapping, optimizing, imputing, inferring, labeling, identifying, clustering, excluding, simulating, modeling, assessing, merging, processing, aggregating, and/or calculating.

There is a significant body of work exploring how automated decision-making systems can harm clients (see “Poverty Lawgorithms” by Michele Gilman; “Automating Inequality” by Virginia Eubanks; “Extreme Poverty and Human Rights,” United Nations), including the use of algorithms for determining the level of care and eligibility for services for individuals living with disabilities. Automation in these systems introduces potential for bias, risk for mistakes, and a potential for overprioritization of computer system assessments over human judgment. Upturn’s recent report found that algorithms in use across different states do not provide objective measures of need; an individual might be deemed eligible under one state’s algorithm and ineligible in another. Digital systems also encode policy choices, including the potential for passing on bias.

The Benefits Tech Advocacy Hub Case Study Library highlights examples of harm related to benefits technology automation. While not specific to integrated benefits systems, the case studies offer relevant documentation about problems stemming from prior implementations.

- Translation errors and interpretations

For a computer system to enable eligibility determinations, policy must be translated into computer code—a process that is vulnerable to errors, as well as subjective interpretation on behalf of the person doing the translation. As legal scholar Danielle Citron explained in 2008, “although programmers building automated systems may not intend to engage in rulemaking, they, in fact, do so. Programmers routinely change the substance of rules when translating them from human language into computer code.”

When rules are encoded in ways that do not accurately reflect the rule’s original meaning, individuals’ benefits may be impacted. For example, it was discovered during the 2023 public health emergency unwinding that systems in 29 states incorrectly evaluated Medicaid and CHIP renewals by verifying eligibility at the household level, rather than the individual level, resulting in wrongful terminations of benefits for hundreds of thousands of children on CHIP in addition to adults on Medicaid.

Legal scholars have developed frameworks to address interpretive challenges for translating law into code, but interpretive issues persist even when translation teams include both computer scientists and legal experts. Research suggests that the translation process itself is likely to produce errors, and must be approached with a degree of caution. As IEE systems include multiple benefits programs, the potential risk of translation errors is magnified.

- Lack of transparency in existing systems

When errors are found in state systems, it is often challenging to identify their source. Because many systems operate in close collaboration with one or more external vendors, states and the public can have limited access to the computer systems, rules databases or engines, and algorithms used to make determinations. In our rules communication research, we have found that neither the U.S. federal government nor any states currently have openly accessible eligibility rules as code. Upturn’s 2025 report emphasized how challenging it can be for members of the public to access information about how a government system operates and assesses eligibility. As illustrated by a 2024 Federal Trade Commission complaint brought by the National Health Law Program, the Electronic Privacy Information Center, and Upturn regarding Deloitte’s Medicaid system in Texas, issues are most often apparent after a significant number of individuals are impacted.

- Data consolidation

In the past several years, state agencies and civic technology organizations have explored how data sharing can be used to enable streamlined benefits enrollment and recertification (e.g., Center on Budget and Policy Priorities 2017, Benefits Data Trust 2023, Benefits Data Trust and the Center for Health Care Strategies 2023). However, as we reported in our first publication in this research series, “Implementing Benefits Eligibility + Enrollment Systems: State Responses to H.R. 1”, some states are rethinking how they use and store data for their IEE systems. To operate an integrated system, states may share data between agencies in charge of different programs, such as the agencies that manage SNAP and Medicaid programs. However, some states are reconsidering the risks of co-locating data and consent processes, particularly in light of recent events, such as the Trump administration providing Medicaid recipients’ data to U.S. Immigration Customs and Enforcement (ICE), and requesting SNAP enrollee data from states and vendors.

Mitigating Risks with Rules as Code

The Digital Benefits Network has previously advocated for a “Rules as Code” approach to translating benefits eligibility rules into computer systems. Rules as Code is defined as an “official version of rules (e.g., laws and regulations) in a machine-consumable form, which allows rules to be understood and actioned by computer systems in a consistent way.” Rules as Code cannot, on its own, solve all potential risks related to IEE systems, but it can help to:

- Alleviate translation issues by making the encoding of rules standardized, more transparent, and easier to review

- Minimize the effort state agencies expend—often through a vendor—to translate rules into their own system by providing access to existing code

- Allow anyone to review the coded rules for accuracy, and provide further transparency into how eligibility determinations are calculated

Explore the Digitizing Policy + Rules as Code page on the Digital Government Hub for research, resources, and demos.

IEE Technologies

IEE systems have complex and varied technical architectures, with multiple components performing different functions. Below, we outline the various functions of an IEE, and the variety of technologies states are currently using to carry out those functions. The list reveals how many different types of technologies are required to support an IEE system, as well as the mix of old and new technical components they contain. States might be simultaneously experimenting with generative AI while continuing to run other functions on comparatively antiquated tools, like COBOL-based mainframe code—revealing how long the timeline for modernization can be.2

“One of the challenges is really moving away from COBOL. And this has been a challenge that I’ve seen over at least the last decade. I’m sure I know we’re not alone in this, but it does seem that we kind of go through these starts and stops on our modernization journeys.”

State Leader

Note: This list documents products that were referenced during our research, in conversations with implementation partners, and desk research. The Beeck Center does not specifically endorse any of the products or services below. This list should also not be considered a comprehensive accounting of all the technology components used in IEE systems.

| Functionality | Examples of Technology and Digital Services Used |

|---|---|

| Apply The application, whether online or otherwise, is a client’s front door to benefits. Every state we spoke to allows clients to apply for benefits online. (States also make applications available through other mechanisms, including allowing people to submit paper applications or apply in-person at an agency office. However, paper applications are often for singular programs as it is challenging to translate the logic to a limited number of pages.) |

|

| Manage documents Many IEE systems allow clients to upload, verify, and manage documents related to their eligibility using an online system. |

|

| Public-facing identity management Many integrated benefits applications require or prompt users to create an account when they apply for benefits and typically require them to log back in to an account when reaccessing a portal to manage their benefits. In addition to verifying information about a client’s eligibility and identity through the use of external data sources, some state applications also require users to take steps to actively verify their identity in order to confirm that the person applying is the intended individual. The DBN has researched and published extensively about the uses of digital identity in public benefits, including: · Our open dataset documenting account creation and identity proofing approaches across states and territories online benefits applications · Our 2025 research examining beneficiary experiences with digital identity processes |

|

| Code and store policy rules in order to assess eligibility Most modernized IEE system’s core functionality relies upon a “rules engine” that stores the coded version of policy rules separate from the public facing application and case management databases. These are used to determine clients’ eligibility for each program. Rules engines apply policy rules to client data to make an initial determination of eligibility, which is then reviewed by caseworkers for a final determination. When policy changes, rules must be updated in the rules engine. Learn more about policy rules as code at the Digital Government Hub. |

|

| IEE system code storage, version control, and issue tracking Some states use tools to help them manage development through storing code and assisting with version control and issue tracking. |

|

| Verify information about applicants and clients IEE systems interface with various external systems (i.e., hubs) to verify information provided by applicants related to eligibility and identity. These commonly include the Federal Data Services Hub, Equifax’s Work Number (which provides employment and income information on individuals), citizenship checks, Social Security checks, and checks to see if clients receive duplicate benefits from other states. |

|

| Store and map applicant data across programs Several states utilize a “master person index”—a database that creates a single record for each applicant, and maps that to each program they apply to. When shared across agencies, this reduces the need for applicants to share the same information over and over again. (See Washington state’s planning documents for a definition of a master person index.) |

|

| Manage client correspondence Systems send digital and print updates to clients, such as communications about application determinations and upcoming appointment notifications, and may enable clients to initiate appeals. |

|

| Initiate payment disbursement For programs like SNAP, once final eligibility is determined, the IEE triggers the processes to disburse benefits payments to clients. | |

| Manage caseworker tasks IEE systems contain portals or interfaces where caseworkers manage case tasks, like inputting client data and reviewing eligibility determinations. |

|

| Support quality assurance and regression testing IEE teams use various technologies to test that changes to their systems elicit the intended outcomes. |

|

| Quality control IEE systems need to enable data exports and reviews of cases and claims. |

|

| Data, analytics, and reporting Many programs such as Medicaid and SNAP require the collection and reporting of specific metrics for the purpose of oversight and quality assurance. |

|

IEE Stakeholders

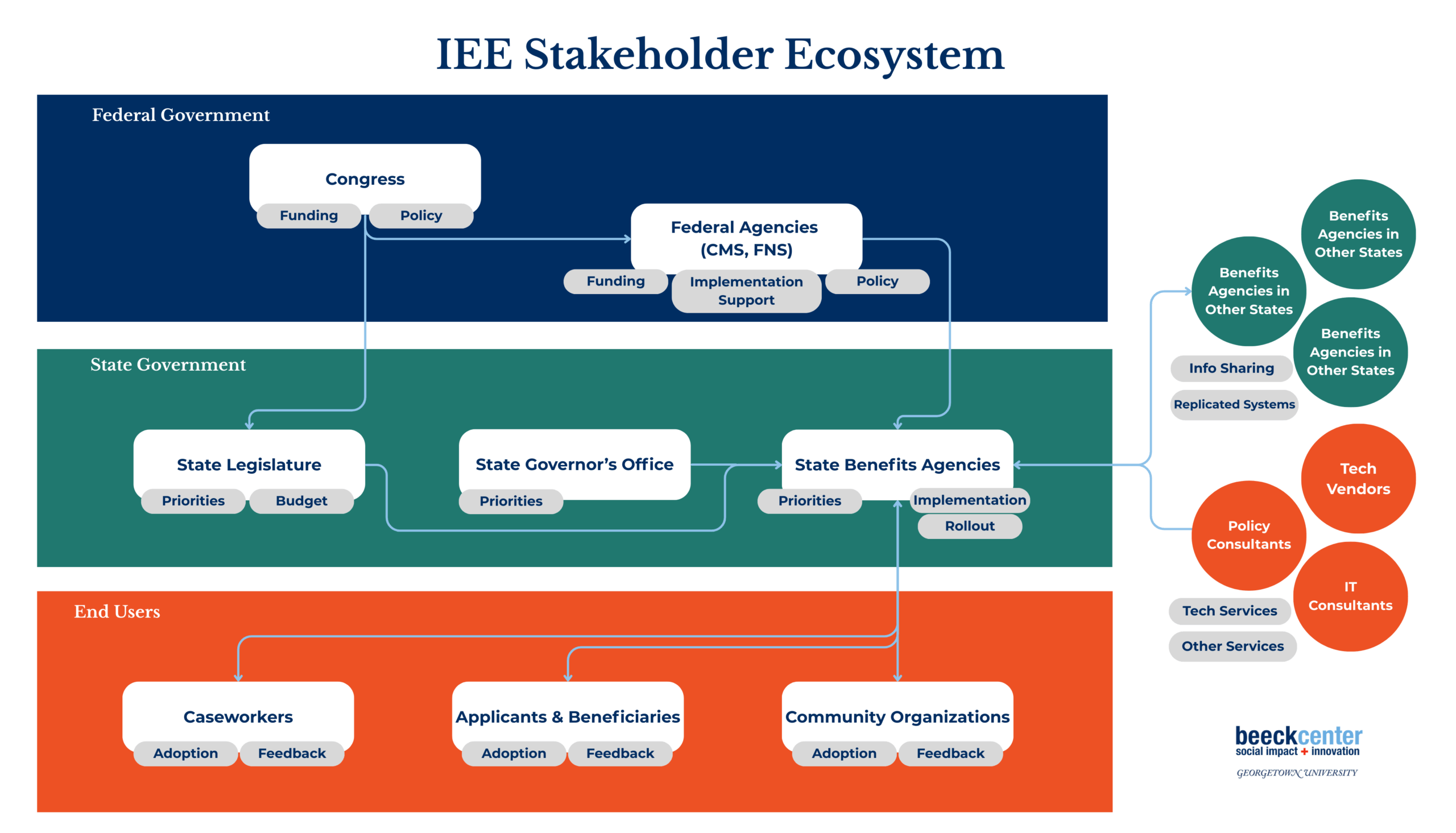

The IEE Stakeholder Ecosystem

IEE systems operate within a complex stakeholder landscape in which numerous entities and individuals hold varying levels of influence over decision-making, resourcing, and project priorities. Some stakeholders exercise direct control over funding and strategic direction, while others contribute technical expertise or end-user perspectives. Some stakeholders play critical roles in pushing modernization forward at the state-level, while others are crucial for supporting clients once the system is live. Each state we spoke to described its own unique configuration of stakeholders, many of whom may have different or even competing priorities.

In the diagram below, we map the entities and individuals that came into view through our research, as well as some of their interests and interactions, as a dynamic stakeholder ecosystem.

Ecosystem Interactions

Our conversations with states revealed details about how information and influence flow across this ecosystem. Some key interactions are below.

- Federal Entities → States and State Benefits Agencies

IEE systems are not siloed from federal policies; they are directly informed by them. States were relatively consistent in their descriptions of how policy influences IEE system development, and how information travels between federal agencies and state agencies.

- Congress passes legislation that shapes benefits policy, and thus the benefits that agencies later implement.

- Federal agencies like the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) help states interpret and implement policy changes by issuing guidance, providing technical assistance, reviewing planning documents, and allocating funding. States must also report changes to program operations and get approval from federal agencies for certain aspects of their system implementation.

“Most of our policy updates come from CMS. … They tell us what to do and then we implement it.”

State Leader

“We’ll also engage specifically with the federal government if we have questions. So, [for example], during the [Medicaid] unwinding, several states had questions around how they were doing passive renewal for the Affordable Care Act, so policy engaged directly with CMS to say, ‘We understand you said X. Here’s a variation of X. … What are your feelings about this?’”

State Leader

- When a single system touches multiple programs, states are also dependent on guidance from several distinct agencies to interpret and implement policy changes.

“We think about these things in such silos. We think, ‘The bill changed this in SNAP, it changed this in Medicaid.’ But our households are not in just one strata. They sit across maybe all of them. … The household that now has to do expanded SNAP work requirements already had to do TANF Work First work requirements, and now maybe has Medicaid work requirements. We need to look across all three and say, ‘Do they need to do something different for each program or the same for each program? How do we build with a horizontal look in mind?’”

State Leader

- Federal agencies fund some of a state’s IEE development through annual appropriations and specific grants. Often, states submit Advanced Planning Documents (APDs) to the federal agencies that oversee their programs to request prior approval of proposed development from those agencies and receive the agencies’ financial support. How funding flows from federal agencies also shapes what system development looks like. One state discussed how its reliance on CMS’ 90/10 funding to improve its eligibility system meant it could not procure its ideal rules engine. Given that CMS had several requirements for the rules engine’s features, the state purchased a rules engine that required its development partners to make updates even though the state envisioned enabling its business team members to make updates.

“The fact is that our funding is through Advanced Planning Documents with the federal government, and those come on two-year cycles. So, we align our roadmap with what we’re requesting every year to cover a two-year period.”

State Leader

Our “Implementing Benefits Eligibility + Enrollment Systems: State Responses to H.R. 1” report discusses how states are responding to the sweeping federal changes to SNAP and Medicaid under H.R. 1., including how federal agencies fund administrative costs of programs.

- State Legislature → State Benefits Agencies

State legislatures exert significant influence over the direction of IEE systems, both by setting program policy and requirements and by distributing funds for program administration and technology.

- State benefits administrators responsible for IEE systems must respond to legislative changes, and at times must work to build buy-in among legislators for system changes and technology modernization. This requires a nimble approach to recalibrating priorities and work plans.

“[There might be a] state legislative session that results in, ‘You now have to apply this change in the next two months in order to meet the new legislative requirements from the state.’ We’re able to apply some of those changes pretty quickly, and then just kind of adjust with the backlog as to how we’re moving things in and out of what gets done.”

State Leader

- Elections and changing administrations can shift leadership priorities, and introduce unknowns and interruptions to long-term workplans. This can be particularly complicated for the development of IEE systems, which touch multiple programs that might be implicated in different ways.

“(An) administration change is really concerning for us, because you’re going to have a whole new group of people that will be joining us and trying to navigate them through, and then getting them up to speed.”

State Leader

- Governor’s Office → State Benefits Agencies

The Governor’s Office approves or vetos the state budget after it passes the legislature, and also informs priorities that the legislature funds and state benefits agencies must act upon.

“Our state agency that is responsible for essentially helping to set statewide performance metrics… with the transition of a new governor in January, also transitioned their focus to customer experience… and government efficiency. We’re awaiting any moment… a new executive order to come out from our governor’s office that is related to customer experience… We will have new performance metrics that are identified for us across organizations… to measure success. So, we will pivot and adapt, and adopt those in any way we can.”

State Leader

- Since agency work must coordinate with the governor’s priorities, the success or failure of technology systems can be reflected back on the administration.

“All of the energy from leadership and from technology is focused on trying to keep that system up and running. … Nobody wants to walk away from it, and the administration doesn’t want to see it as a failure.”

State Leader

- State Benefits Agencies ↔ State Benefits Agencies (within the same state)

IEE systems host programs from various agencies, requiring coordination between distinct agencies and across offices within the same agencies. This adds complexity related to priorities, work styles, logistics and communication, and more.

“As we do this work, [we] really are responsible for doing it for three agencies… There’s a Medicaid agency, there’s a human services agency that I also sit in … and then there’s a child care agency. … So, I spend a lot of time coordinating their priorities, then working with the Governor’s Office to make sure, ultimately, we can take their state plan policy, implications, budget restraints… and line them up into a strategic plan that we know what we’re doing and how we’re doing it.”

State Leader

- States that are building a master person index must build buy-in across program teams and agencies. The more agencies that participate in the effort, the greater the impact.

“We have stood up a master person index… I think we’ve onboarded three to four organizations… So, that is an IEE effort to try to get more agencies using that, so that we’ll have broader use of that data across the state.”

State Leader

- State Benefits Agencies ↔ State Benefits Agencies (in other states)

To develop robust IEE systems, states are sharing knowledge and tools with other state governments.

- Some states are engaging in a culture of collaboration across state lines. With many states currently at work on IEE projects, agencies leading them seek to benefit from lessons learned and resources and methods that have already been developed—if those states are willing to share. One state is developing a questionnaire to send to other states with low or significantly reduced SNAP error rates to learn from their experiences, hoping those states will also engage in a working group to share their learnings. The same state is taking a similar approach to learn from states that have already implemented a self-employment standard.

- One state mentioned being part of a regular email group with representatives from 43 states and territories that have integrated systems.

- Some states mentioned purchasing systems from vendors that were originally implemented in other states—and suggested that repurposing technology in this way has the potential to slow down innovation, but other states noted this practice allows them to avoid starting from scratch.

- State Agencies ↔ Vendors

As we note below in our discussion of key roles involved in updating and maintaining IEE systems, vendors play a significant role, in some cases performing much of the day-to-day work and maintenance. Vendors hold significant subject matter expertise and based on contract agreements, may determine the cadence at which changes and updates can be made. The broader vendor ecosystem also shapes what options state benefits agencies have when procuring outside technology or services for their systems.

- State Agencies ↔ End Users (Caseworkers, clients, and community organizations)

States see caseworkers, clients, and community organizations as key stakeholder groups to both consult and keep informed. The states we spoke to described using a variety of methods to reach end users like clients and frontline staff.

- One state recently did a month-long pilot in which they posed a short survey to clients at the end of phone calls; another has a permanent internal testing lab that engages frontline staff and clients in assessing new technology.

- Another state described two working groups—one composed of clients, the other of frontline staff—that meet monthly to provide feedback on and generate ideas for in-progress technologies and help the agency prioritize changes. Another described working with community organizations to reach clients and engage in testing and collaborative work on new system designs.

“We do a significant amount of testing out in the field with real customers. Some of this is coordinated through our community-based organizations that will actually bring people into the testing lab, or we’ll go and meet them for a testing session at one of the local departments of social services… This is the one that is most fun, but is also subject to different results, depending on how crowded and available people are.”

State Leader

“We don’t do this work alone. We do this work in coordination with other state agencies and organizations—and with a myriad of community and local parties to be a conduit for our customers, should they need support.”

State Leader

Project Teams and Roles

Besides being complex, multi-layered technology products, IEE systems engage with multiple programs and all of the complex, fluid policies that pertain to each. As such, they require input from many teams—each providing crucial insight, experience, and access—in areas ranging from technology and policy to programs and user experience. In our research, we spoke to people across a range of roles, including:

- Agency leaders (deputy commissioners, assistant secretaries, chiefs of staff)

- Heads of modernization, organizational change management, digital experience, innovation, automation, and integrated eligibility

- Product owners and managers

- Program managers

- Project managers

- Policy and business analysts

- System architects

Our interviewees also mentioned additional important roles, including:

- Designers

- Testers

- Communications team members

- Trainers

Our interviews also underscored the range of agencies involved, depending on how oversight for benefits programs was distributed across distinct agencies. This typically involved human services agencies, health and human services agencies, and in some cases, state Medicaid agencies.

In each conversation, we asked how people understood their own role and how it related to the work of other team members. Key insights are below:

- Team composition depends on how states organize their programs.

In some states, a single agency administers Medicaid, SNAP, TANF. In other states, different agencies administer Medicaid and SNAP, but still share a single application portal or technology system. When a single agency manages an IEE system, staff may work across multiple programs. When multiple agencies jointly manage the system, individual staff members may be more likely to specialize in a single program.

For more on the structure of human services agencies across the country, see the Urban Institute’s 2022 report “What Are Human Services, and How Do State Governments Structure Them?”

- IEE systems are built and managed by people across multiple functions, including policy staff, business analysts, product owners, communications staff, designers, and technical and testing teams. Some work may involve roles within a single agency, while others will require coordination across multiple teams or agencies.

- States report that early coordination with policy teams is essential for understanding and approving changes.

- IEE systems require regular interaction and collaboration between teams and agencies.

States reported diverse approaches to IEE project governance, ranging from single-agency initiatives led by functional teams to multi-agency collaborations that convene on a regular schedule or as needs arise.

- Several states described IEE system work as collaboratively led by governance teams or “coalitions” made up of representatives from various relevant teams and/or agencies. These build shared ownership and consensus, while presenting some challenges related to inevitable differences in priorities and timelines.

“The primary system of record for eligibility is housed in a partner agency, and it houses multiple programs, SNAP, Medicaid. … We’ve continuously run into, ‘How do we prioritize for the people who actually have to do the programming for the policy changes?’ We’ve tackled it by trying to get a cross-agency team together to identify how [we’re] going to prioritize, based upon what’s required versus what’s desired. Is it a federal requirement that has a deadline attached, or a state requirement? Or is this just an enhancement that we want to make? What resources do we have available? People, time, money—all the rest of it. And I will say we still haven’t figured out the sweet spot.”

State Leader

- States described how these groups convene to review change requests and new system projects. In doing so, they assess impacts across teams, and often have regular meeting dates to discuss and vote on changes proposed by each team. However, the cadence can vary widely—from weekly to multi-week sprints and quarterly or even ad hoc sessions. However, minor changes may be handled by a smaller team: “We have regular maintenance items, and those are worked out with a smaller group with less governance.”

“We have a weekly cadence with the [tech vendor] as well as [agency] partners to outline upcoming change requests or prioritization and align those teams with ours to ensure that we’re able to meet the implementation date with those changes.”

State Leader

“We have a robust governance group with representation from three agencies… Quarterly, the groups look [at our strategic roadmap] and start to project out what’s going to need to be on there… So, any change requests can be brought forward by these key program sponsors. They take them forward and the committee votes on it… The important part of this is, it’s a living document.”.

State Leader

- Others described responsive working models, where different functional teams take on distinct tasks and also come together to solve for specific change requests, as needed.

“The [Medicaid] policy team, they coordinate with our policy team and they work together first to make sure that we’re all in sync on what the change is going to be… Then we bring the systems people together… and they write the system requirement that includes the [new] user story. It gets reviewed, and depending on the complexity of the policy, there may be JAD [joint application design] sessions coordinated between [all the teams]. And we have lead players on both sides that will come together, and they will participate in the JAD sessions with the vendor to design how the change needs to be created and what the ultimate result is to make sure it meets our need[s]—because they’re not going to tell us. We’re going to tell them.

State Leader

- One state described how a single individual acts as a kind of “glue” across policy, tech teams, and vendors, based on deep personal expertise.

“We have a technology expert who actually kind of grew up knowing the programs. So throughout his whole career he’s really been kind of the glue. He knows the programs and the policies and has followed that a lot… he’s helping policy managers identify what the system needs. And then he’s also working with our technology partners at [agency] and [agency] for [our IEE system] and then the MMIS [Medicaid Management Information System], so making sure that when those systems are impacted by a policy change, making sure those changes happen and then get prioritized.”

State Leader

- Regardless of their chosen operating model, IEE systems require regular collaboration between program teams to assess potential impacts of program-specific changes to a shared system.

- One state described an “opt-in” model that gives program teams transparency into projects led by other programs that are impacting the system.

- Another state has a dedicated team that updates and maintains its IEE. As a result, this team views the different state agencies that run the programs on the IEE as its stakeholders. The team described bringing policy teams together to discuss consequences of major changes.

“Each of the program areas can onboard our own changes. So we have a process called ‘opting in,’ where we all get to see all of the projects that other program areas are considering and have the opportunity to say, ‘I need to be part of this.’ So, anything that SNAP is considering, my division has an opportunity to look at it and say, ‘That might impact us. We need to be part of this project,’ or ‘Hey, can we talk about this and figure out what the ramifications are.’”

State Leader

“Because we have multiple agencies and administrations that are part of the overall organization, they all have their own policy teams that we work with closely on any changes… We start with the individual policy teams, so that they can give direction from their agency or administration’s perspective… Then we will take that information collectively and bring together the groups to understand the impacts cross-administration… One of the challenges we have is one policy may have a negative or unintended impact on another program in the way that we’re trying to consolidate the single application and integrated eligibility process. So, we’ll run through the evaluation of what those impacts are, [and] how they would be applied within the rules engine that we’re using to determine.”

State Leader

- Vendors play an outsized role in technical operations.

Many states described close and longstanding relationships to vendors, which play key roles in the technical development and maintenance of their IEE systems.

- Many states rely on vendors to maintain and update their IEE systems. There are few vendors in this space, and states frequently contract with vendors for a five- to ten-year period. As states continue to ask vendors to make updates to their outdated systems, vendors accumulate more knowledge about how those systems run, which further ties states to contracts with those vendors. Due to this entrenchment, vendors have limited incentive to innovate, which contributes to these systems becoming outdated.

“The last time (our IEE system) was put out for re-procurement, this incumbent vendor was the only vendor that bid. So, we’ve been with the same vendor for over 15 years, and that’s created this situation where a lot of the knowledge about the system resides with them. And then also, the system itself is sort of what gets built up over 15 years with the same vendor.”

State Leader

- Outside vendors deliver work on system development, and also play a key translational role in helping states plan for upcoming changes. One state shared that most of their IT staff are contractors.

“We rely on our vendor SMEs (subject matter experts) to help us understand what we’re doing.”

State Leader

- But, not all states rely on vendor support. As one state told us:

“We serve as the state system integrator. In many cases, these types of programs are often supported by vendor-based system integrators. … We’ve taken an alternative approach where we, as state employees, serve as the team that actually builds all of these applications or performs the integration with COTS [commercial, off-the-shelf] products and manages the day-to-day of the overall benefits access platform.”

State Leader

- Project operations depend on highly specialized institutional knowledge held by team members—both internal and contracted. Members of IEE teams bring deep knowledge of program areas, policy, and institutional history. Many of the leaders we spoke to have decades-long tenures in their agencies, with some even working their way up from caseworkers—a trajectory that offers a unique expertise.

“It’s really just making sure the right players are there at the meetings to create the business requirements document, which is kind of a high-level policy document before the technical design. … We’re lucky, we’ve got players that have been doing this a long time. I’m at 20 years, my coworkers [are] at 20 years. The people we work with, our vendor, we’re at 10-ish years, if not more.”

State Leader

One state described how a single individual acts as a kind of “glue” across policy, tech teams, and vendors, based on deep, accumulated expertise.

“We have a technology expert who actually kind of grew up knowing the programs. So, throughout his whole career he’s really been kind of the glue. He knows the programs and the policies and has followed that a lot… He’s helping policy managers identify what the system needs. And then he’s also working with our technology partners [at multiple agencies] … for [our IEE system] and then the MMIS [Medicaid Management Information System], so making sure that when those systems are impacted by a policy change, making sure those changes happen and then get prioritized.”

State Leader

This valuable depth of knowledge takes a long time to develop, and preserving and sharing it is not straightforward. Some states expressed concern about the fact that projects are so dependent upon specific individuals or vendor relationships.

“The amount of knowledge that our policy folks have to have about our system is immense and then it takes a long time to have that knowledge. It is a very long process, mostly done through documents and conversation. And then there’s a lot of reliance on the vendor.”

State Leader

States use varying technology, timelines, and staff to update and maintain their IEE systems. They adapt approaches for their specific contexts, with no states using the exact same ways of working. We observed states in the same geographic regions with roughly similar populations using entirely different staff and technology, and working in radically different ways. These distinct differences make developing a single, nationwide solution or process challenging. However, by better understanding the range of structures, we can identify commonalities and shared possibilities.

What’s Next

In the next publication in this series, we will delve into the processes stakeholders use to manage and maintain IEE systems, including assessing policies, setting priorities, and communicating with clients. The publication will also explore pain points in the process that emerged in our research, and how these challenges are informing new modes of working.

Get in Touch

The Digital Benefits Network is here to help. We are able to connect you to peer state leaders, nonprofits seeking collaboration, and the latest resources and research. Get in touch at digitalbenefits@georgetown.edu.

You can review our other publications in this series to:

- Understand how state agencies are responding to federal policy changes and their impacts on IEE systems

- Learn more about the processes involved in updating and maintaining state IEE systems, identify pain points, and learn about alternative approaches that states have considered

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the state leaders who spoke with us about their IEE systems and how they are responding to federal changes.

Thank you to Sabrina Toppa for copy-editing.

Citation

Cite as:

Rachel Meade Smith, Jason Goodman, Ariel Kennan, and Elizabeth Bynum Sorrell “Implementing Benefits Eligibility + Enrollment Systems: Key Context,” Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation, December 9, 2025, https://digitalgovernmenthub.org/publications/implementing-benefits-eligibility-enrollment-systems-key-context.

Footnotes

- According to Code for America’s 2025 Benefits Enrollment Field Guide, nine states added one or more programs to their integrated benefits applications between 2019 and 2025. Today, 15 states now offer four programs in a single application, and five states now allow applying for Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) Medicaid, SNAP, TANF, Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP), and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) in a single application. ↩︎

- COBOL (common business-oriented language) is “a high-level, English-like, compiled programming language that is developed specifically for business data processing needs.” The use of COBOL in benefits systems was widely covered during the pandemic, when COBOL-based unemployment insurance (UI) systems faced significant challenges meeting the sudden increase in claims (see for example: Wire, C. (2020, April 8). Wanted urgently: People who know a half century-old computer language so states can process unemployment claims. WTIC. https://www.fox61.com/article/money/unemployment-backlog-connecticut-computer-language-cobol-coronavirus-covid-labor-department-mainframe/520-4299027f-88dd-4c2f-9fe3-f9118387cb3f; Allyn, B. (2020, April 22). “COBOL cowboys” aim to rescue sluggish state unemployment systems. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2020/04/22/841682627/cobol-cowboys-aim-to-rescue-sluggish-state-unemployment-systems; Kelly, M. (2020, April 14). Unemployment checks are being held up by a coding language almost nobody knows. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2020/4/14/21219561/coronavirus-pandemic-unemployment-systems-cobol-legacy-software-infrastructure). The issue resurfaced in some states during the 2025 government shutdown (Pittman, A. (2025, November 21). Full SNAP benefits further delayed in mississippi due to decades-old systems. Mississippi Free Press. https://www.mississippifreepress.org/mississippians-still-waiting-on-full-snap-benefits-as-decades-old-systems-cause-further-delays/).

Michael Navarrete at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta (2025) also provides an analysis of aggregate consumption during the pandemic in states with COBOL-based UI systems. In these states, where claimants encountered greater administrative difficulties accessing benefits and delays, aggregate consumption fell more than in non-COBOl states. (Navarrete, M. A. (2025). COBOLing Together UI Benefits: How Delays in Fiscal Stabilizers Affect Aggregate Consumption. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Working Papers, 2025(14). https://doi.org/10.29338/wp2025-14).

↩︎

Sources

- Allyn, B. (2020, April 22). “COBOL cowboys” aim to rescue sluggish state unemployment systems. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2020/04/22/841682627/cobol-cowboys-aim-to-rescue-sluggish-state-unemployment-systems

- Alston, P. (2019). Extreme Poverty and Human Rights. United Nations General Assembly. https://docs.un.org/en/A/74/493

- Ambegaokar, S., Neuberger, Z., & Rosenbaum, D. (2017). Opportunities to streamline enrollment across public benefit programs. In Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/opportunities-to-streamline-enrollment-across-public-benefit

- Brown, L. X. Z., Richardson, M., Shetty, R., Crawford, A., & Hoagland, T. (2020). Challenging the Use of Algorithm-driven decision-making in Benefits Determinations Affecting People with Disabilities. Center for Democracy and Technology. https://cdt.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/2020-10-21-Challenging-the-Use-of-Algorithm-driven-Decision-making-in-Benefits-Determinations-Affecting-People-with-Disabilities.pdf

- Case studies library. (n.d.). Benefits Tech Advocacy Hub. Retrieved November 5, 2025, from https://www.btah.org/case-studies.html

- China, C. R., & Goodwin, M. (n.d.). COBOL. IBM. Retrieved November 5, 2025, from https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/cobol

- Citron, D. K. (2008). Technological Due Process. Washington University Law Review, 85(6), 1235–1313. Washington University Open Scholarship. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1166&context=law_lawreview

- CMS has released 90/10 funding for states to improve their eligibility systems for Medicaid. Will that funding continue? (n.d.). Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved November 5, 2025, from https://www.medicaid.gov/faq/2020-04-16/94591

- Complaint and Request for Investigation, Injunction, and Other Relief (Federal Trade Commission). Retrieved November 5, 2025, from https://healthlaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/NHeLP-EPIC-Upturn-FTC-Deloitte-Complaint.pdf

- Escher, N., Bilik, J., Banovic, N., & Green, B. (2024). Code-ifying the law: How disciplinary divides afflict the development of legal software. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 8(CSCW2), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1145/3686937

- Eubanks, V. (2018). Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor. St. Martin’s Press. (2018)

- Fergusson, G. (2023). Outsourced & automated. In EPIC – Electronic Privacy Information Center. https://epic.org/outsourced-automated/

- Gilman, M. (2020). Poverty lawgorithms. Data & Society. https://datasociety.net/library/poverty-lawgorithms/

- Gjika, T., Kahn, J., Khan, N., & Vuppala, H. (2019). Insights into better integrated eligibility systems. McKinsey. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-sector/our-insights/insights-into-better-integrated-eligibility-systems

- Godfrey, N., & Burdon, M. (2024). Fidelity in legal coding: Applying legal translation frameworks to address interpretive challenges. Information & Communications Technology Law, 33(2), 153–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600834.2024.2312620

- Hahn, Heather, Pratt, E., Lawrence, D., Aron, L. Y., Martinchek, K., Williams, A. R., & Sonoda, P. (2022). What are human services, and How Do State Governments Structure Them? Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2022-12/What%20Are%20Human%20Services%20and%20How%20Do%20State%20Governments%20Structure%20Them.pdf

- Higham, A. (2025, September 22). Trump administration barred from collecting SNAP data in 21 states. Newsweek. https://www.newsweek.com/trump-administration-barred-collecting-snap-data-21-states-2133566

- Humphries, J. (2023). Data Coordination at SNAP and Medicaid Agencies: A National Landscape Analysis. Benefits Data Trust, Center for Health Care Strategies. https://digitalgovernmenthub.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/bdt_chcs_datasharing.pdf

- Kelly, M. (2020, April 14). Unemployment checks are being held up by a coding language almost nobody knows. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2020/4/14/21219561/coronavirus-pandemic-unemployment-systems-cobol-legacy-software-infrastructure

- Kindy, K., & Seitz, A. (2025, July 17). Trump administration hands over nation’s Medicaid enrollee data to ICE. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/immigration-medicaid-trump-ice-ab9c2267ce596089410387bfcb40eeb7

- Medicaid Renewals Playbook. (n.d.). United States Digital Service. Retrieved December 5, 2025, from https://usds.github.io/medicaid-renewals-playbook/ex-parte-renewals/individual-vs-household.html

- Mohun, J., & Roberts, A. (2020). Cracking the code: Rulemaking for humans and machines. In OECD Working Papers on Public Governance. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/cracking-the-code_3afe6ba5-en.html

- Navarrete, M. A. (2025). COBOLing Together UI Benefits: How Delays in Fiscal Stabilizers Affect Aggregate Consumption. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Working Papers, 2025(14). https://doi.org/10.29338/wp2025-14

- Osman, M., Paul, E., & Weil, E. (2025). Calculated need: Algorithms and the Fight for Medicaid Home Care: A Comparison of Five States’ Eligibility Algorithm. In Upturn. https://www.upturn.org/work/calculated-need/

- Pittman, A. (2025, November 21). Full SNAP benefits further delayed in mississippi due to decades-old systems. Mississippi Free Press. https://www.mississippifreepress.org/mississippians-still-waiting-on-full-snap-benefits-as-decades-old-systems-cause-further-delays/

- Pradhan, R., & Liss, S. (2024, June 24). Medicaid for millions in america hinges on deloitte-run systems plagued by errors. KFF Health News. https://kffhealthnews.org/news/article/medicaid-deloitte-run-eligibility-systems-plagued-by-errors/

- Preliminary Overview of State Assessments Regarding Compliance with Medicaid and CHIP Automatic Renewal Requirements at the Individual Level, as of September 21, 2023. (2023, September 21). Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2023-09/state-asesment-compliance-auto-ren-req_0.pdf

- Richardson, R. (2022). Defining and Demystifying Automated Decision Systems. Maryland Law Review, 81(3), 785–836. Digital Commons. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3811708

- Saffold, J. Y., Gibbons Straughan, B., & Weiss, A. (2023). Data Sharing to Build Effective and Efficient Benefits Systems: A Playbook for State and Local Agencies. Benefits Data Trust. https://digitalgovernmenthub.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/data-sharing-to-build-effective-and-efficient-benefits-systems_january-2023.pdf

- The Benefits Enrollment Field Guide. (2025). Code for America. https://codeforamerica.org/explore/benefits-enrollment-field-guide/

- Wire, C. (2020, April 8). Wanted urgently: People who know a half century-old computer language so states can process unemployment claims. WTIC. https://www.fox61.com/article/money/unemployment-backlog-connecticut-computer-language-cobol-coronavirus-covid-labor-department-mainframe/520-4299027f-88dd-4c2f-9fe3-f9118387cb3f